Why We’re Transforming our Image of Nature as a Resource

Part 2

I’ve run into a stressful time recently, and when I say that I mean more stressful than usual. It was a beautiful morning with a fresh layer of snow that came overnight. It was foggy, too, which is unusual here. The birds were busy singing, chatting, and flying. As I walked my dogs I tried to feel connected to everything around me, but it was hard because of all the things on my mind. It’s easy to feel disconnected from nature. Our lives are busy, our minds are busy.

One disconnect is to see nature as a resource purely for our benefit. Wood for homes, metals to mine, beauty and recreation for our vacations. This places us outside of nature. Yes we benefit from it, but this view limits our understanding of our world and we’re only seeing half of it. Reconnecting with nature could mean that we see all its beings as our kin, that we’re all interconnected and interdependent, and that each of us has an important role in this world. Each of us is surviving, thriving, and having a different perspective on what’s important. Thinking this way, loneliness is replaced with a sense of being part of something bigger.

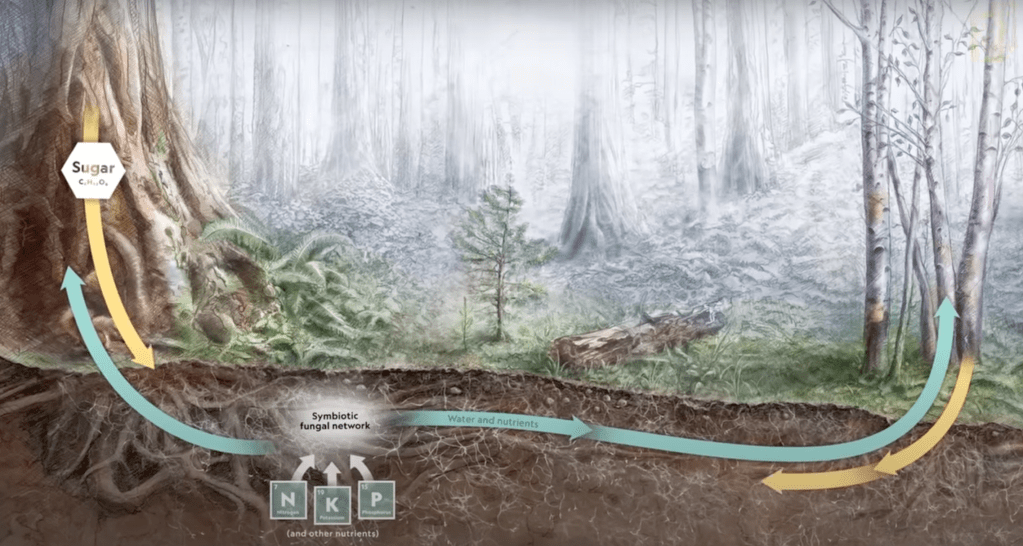

This idea of interconnectedness is described well by stories throughout nature. Take the story of the mycorrhizal network. Underground, tree roots and fungi mycelium (threads) connect—actually fuse—and share resources. We try to understand it by observing and attaching metaphors to it, like the Wood Wide Web or stock market exchange. As we delve deeper into the study of this relationship between fungi and trees, we realize it’s like nothing else.

Without the fungal network, trees and their seedlings won’t grow as well, if at all. The fungi benefit, too. Because fungus doesn’t photosynthesize, it needs the trees’ help to access sugary carbon for survival. In exchange, trees receive more nutrients from the soil from the fungi. The fungi connects to multiple trees and goes for miles, connecting trees to each other. The trees communicate with each other, too, sharing resources during seasons or times of stress.

This is proof of the basic idea of ecology: that there are relationships between organisms that extend to populations, communities, ecosystems, from the ocean trenches to the mountaintops to the air.

David Hinton wrote in Hunger Mountain that we began to lose our connection with nature when we identified ourselves as separate beings with our language. As soon as there was an “I” we saw ourselves as independent from each other and our environment.

Robin Wall Kimmerer describes how her ancestors’ language acknowledges a world where everything is alive and connected. “Life pulses through all things, through pines and nuthatches and mushrooms. This is the language I hear in the woods, this is the language that lets us speak of what wells up all around us.” Kimmerer ponders that we would be less lonely if we could consult with the beavers, the water, and the trees on how to take care of the world instead of being its oligarchs.

Merlin Sheldrake wonders how we could expand our concepts so that other organisms are neither “it” or “she/he” and we may not understand them or put them in a category we’ve created, but instead we can observe them. Using human, machine, or even plant metaphors may be helpful in conceptualizing a fungal network, for example the word “network” makes us think of things in our lives we understand. But they are not the same. Sheldrake wrote, “We have to shift perspectives and find comfort in—or just endure—uncertainty.”

Letting go of the misconception that we can control everything can be freeing. It’s frustrating at first, because we are told we can control our destiny and that if we try hard enough we will get what we want. Even if we can’t control everything, we can control what we do. There are billions of inhabitants—fungi, owls, dogs, humans—all doing their thing. As a human inhabitant, we can treat the other inhabitants with love, and looking through that lens we can feel more connected to it all.

Get outside and get connected! Here’s just a few organizations that are helping people connect to nature:

Vida Verde—promoting educational equity by providing free overnight environmental learning experiences.

Save the Redwoods – partnering with schools and helping adults plan their visit to a redwood park.

References

Hinton, D. 2012. Hunger Mountain: A Field Guide to Mind and Landscape. Shambhala.

Kimmerer, R.W. 2015. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

Sheldrake, M. 2020. Entangled Life. Random House Books.

Simard, S. 2025. “The Mother Tree.” The Mother Tree Project.

National Geographic. 2025. How Trees Secretly Talk to Each Other in the Forest. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kHZ0a_6TxY

Leave a comment